The Good and the Beautiful

Most people have heard that the Inuit people of the Canadian Arctic have over fifty words for snow. It turns out the Scots and Scandinavians also love snow words and use over four hundred names to describe their winter wonderlands. The Guugu Ymithirr of Australia have no word for right and left but instead use cardinal directions – “There is a bug on your south leg”. Russians do not have a single term for to the range of colors we call “blue” in English, but instead have separate words for different shades of light and dark blue. The Pirahã of the Amazon don’t have words for numbers. They have no money to count and they describe quantities only with “big”, “small”, “many” or “few”. In Italian a mountain is feminine, but a lake is masculine. Any anthropologist or linguist will tell you that a language is not simply a communication tool belonging to a particular group of people, but an intrinsic reflection of culture. It’s easy to see how a language grows from culture, like the importance of having a word for icy, slippery snow if you had to drive your sled on it every day. But it’s also true that a language shapes the way we think and view the world. It’s a bit of the chicken and the egg.

As a native English speaker, one of the interesting (and challenging) things about living in Sicily is that what you hear people speaking is rarely a single language. Of course you mostly hear Italian, but with a Sicilian accent. You also hear Italian mixed with Sicilian; which is not a dialect of Italian but it’s own unique language. And you hear many different dialects of Sicilian. What’s spoken in Palermo is distinctly different than what you’ll hear in Catania, and many words change even between villages less than ten kilometers apart.

One of the first things I noticed both about the language and the culture here is the frequent and varied use of the words “good” and “beautiful”. Yes, this plays right into the American romanticized vision of Italian culture – the treasures of Italian art and design, the sun-baked, pastoral landscape, the intoxicatingly delicious food, the relaxed lifestyle, the beautiful, stylish people. We all bring our filter when we enter another culture and I’m clear, like most cinema-influenced Americans, my confirmation bias for Italy leans towards all things pleasure and beauty related.

But in my day to day experience, there are some real differences in how goodness and beauty are expressed and exchanged through greetings, salutations and compliments. In the US we sometimes say hello to a stranger, a store worker, someone we wait with in a line or pass on a street. But often we don’t say anything at all. Here greetings are said regularly to virtually everyone, and for every part of the day.

buongiorno – good morning

buon pomeriggio – good afternoon (not commonly used, more formal)

buona sera – good evening

buonanotte – good night

buon pranzo – good lunch

buona cena – good dinner

buon apettito – enjoy your meal (literally “good appetite”)

buona Domenica – good Sunday

buon lavoro – good work

buona fortuna – good luck

buonissimo – very good

Sure, we have all of these words or phrases in English but we don’t put them to use nearly as often as Sicilians do. It’s actually rude to enter a store and not greet people (the owners, workers and other customers) with “buongiorno” or “buona sera”. A meal in someone’s home or in a restaurant never begins without a “buon apettito”, “buon pranzo”, or “buona cena”. If I’m out on a Sunday, or I’m heading back to work, or to have lunch; I’m guaranteed to have several people wish me a “good”…whatever is happening next. My favorite realization of how creatively Sicilians speak “good wishes” was an afternoon I went to the fruit and vegetable shop near our house and a big box of porcini mushrooms had just come in. It was the beginning of porcini season and the owner insisted I try them, very excited to tell me instructions on how to cook them and how fresh and delicious they would taste. As I headed home instead of the usual “Arrividerci. Buon pranzo!”, he said with an enthusiastic smile “Buon Porcini!”.

Just as “good” is sprinkled throughout the day, the word “beautiful” also flavors the conversation in ways we don’t hear in English.

bello / bella – handsome / beautiful

belli – beautiful (plural)

bellisimo / bellisima – very beautiful

beddu / bedda – handsome / beautiful (in Sicilian)

beddi – beautiful (plural – in Sicilian)

bellezza – beauty

bidizza – beauty (in Sicilian)

bella giornata – beautiful day

Even eastern Sicily’s renowned volcano, Mount Etna, is more fondly known by locals as Mongibello or Mungibeddu. In Italian “monte” is mountain and “bello” is beautiful. The Sicilian “Mongi” or “mungi” are a combination of Latin “mons” and Arabic “jebel”, both meaning mountain. So “Mongibello” and “Mungibeddu” both mean Mount Beautiful.

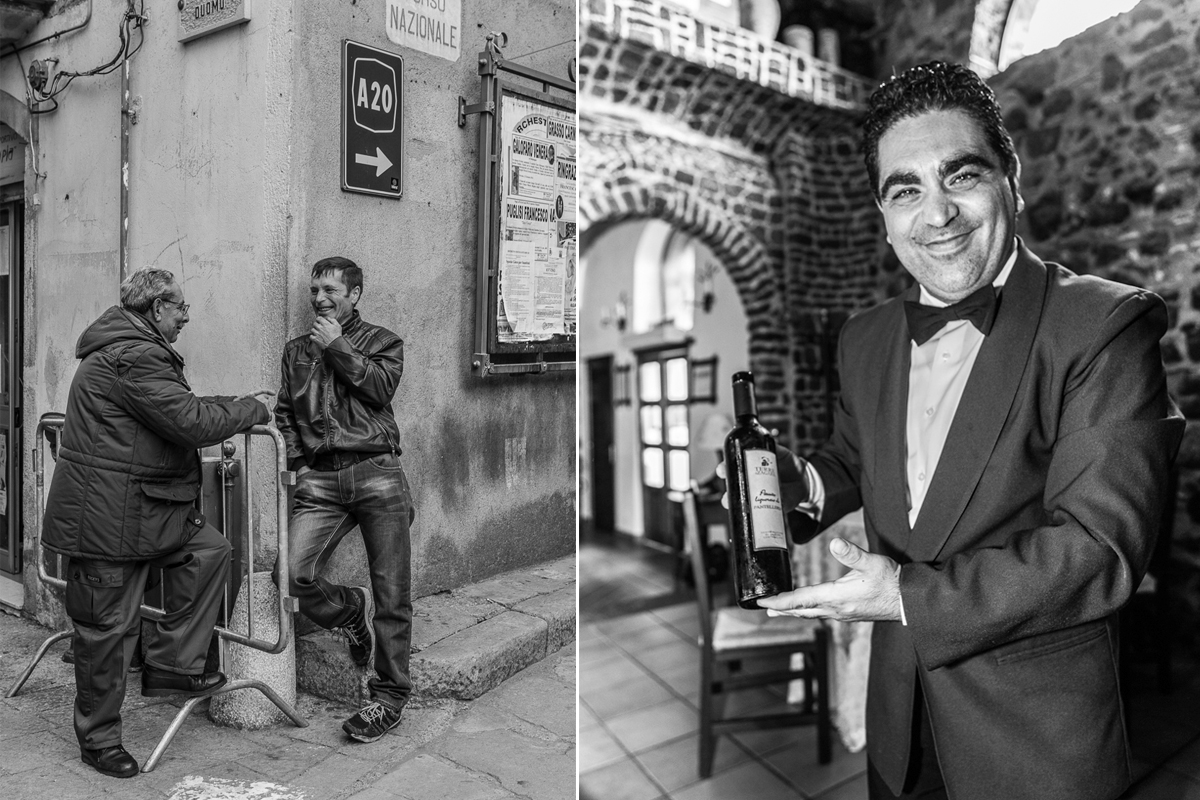

Friends and family of all ages greet each other with “Ciao bella!” for women, and “Ciao bello!” for men. In town we often hear the Sicilian; “Ciau beddu!” and “Ciau bedda!”. Whether you’re talking to your girlfriend, uncle, schoolmate, or grandmother; “hello beautiful/handsome” is a kind of warm, universal greeting. Here’s where the cultural differences become very clear. In English we simply do not tell people we think they are beautiful so often, and when we do describe someone as beautiful or handsome it tends to refer more directly to their physical appearance. Can you imagine your average American man greeting his male friends with “Hi handsome!”? It just doesn’t happen. But here the compliments flow freely across genders and ages and beautiful is not a synonym for pretty and attractive. It’s more about the feeling of appreciation and affection between people; a common term of endearment.

Coming from a different culture and language, hearing good and beautiful so often is a new experience. You feel like a child who didn’t get enough hugs growing up and you’re suddenly receiving affection from everyone around you. In fact, aside from the kind words there’s a high likelihood you’ll get more actual hugs and kisses in Sicily too. Maybe for Sicilians it’s just normal etiquette so it doesn’t have the same effect or meaning. For me, it’s a bit like having your days punctuated with a steady flow of positive affirmations and compliments. It’s like a continuous reminder to acknowledge goodness and beauty; feel it for a moment, exchange it with the people around you. I wonder how the repetition of these words, like the practice of a mantra, affects our perceptions of the world. Would the effect work in reverse? If a Sicilian moves to some far northern, emotionally reserved country would he wither into depression from lack of affection? Probably not, but add being deprived of a real espresso, Sicilian pastries and good olive oil; it could push him over the edge.

On the other hand a Sicilian friend of mine, who’s also a language teacher, said he realized one day how many ways he could think of to say “stupid” in Sicilian. So he started writing them down and came up with over forty different words. He said maybe it was because although Sicilians are generally very tolerant of people’s different cultures, lifestyles, backgrounds; they find it very irritating when someone acts stupid. Whether it’s good, beautiful or stupid – words are not just about the names we call things, but how language is rooted in culture and in our daily life. The real meaning of words comes not just from their literal definitions, but how we choose to live and breathe them.

Until next time, Ciau Beddi!